Published: 24/06/19 13:25 Categories: Microbiology

What do we know about E. Coli?

Escherichi coli is a gram-negative bacterium belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family (such as Salmonella, Shigella and Yersinia, among others). With respect to its morphology, the bacterium has short bacilli shaped as a cane that can present several peritrichous flagella. They are non-sporulated, facultative anaerobic and mesophilic bacteria that develop at temperatures between 20 º C and 40 º C. The optimal growth pH is between 6 and 8.

This microorganism is widely distributed in the digestive systems of warm-blooded living beings (humans and animals); therefore, its presence is used as a main indicator to detect fecal contamination in water and food quality control.

Considered a harmless commensal of bacterial flora, these bacteria constitute approximately 1% of the intestinal microbiome. While most strains present in organisms provide benefits to the host, there is a significant group of strains that are considered pathogenic and can cause serious diseases in humans.

.jpg)

We discovered the pathogenic strains of Escherichia coli

The main difference of this group in terms of innocuous strains lies primarily in the acquisition of specific virulence mechanisms, which give them the ability to produce toxins, express molecules for cell adhesion, capacity for tissue invasion, resistance to the immune system, etc.

Based on these acquired pathogenicity mechanisms, there are 6 different groups or serotypes:

1. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC)

2. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC)

3. Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC)

4. Enterohemorrhagic or verotoxigenic Escherichia coli (EHEC/VTEC/STEC)

5. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

6. Diffusely adherent Escherichia coli (DAEC)

From the entire pathogenic strain group, the enterohemorrhagic serotype (EHEC/STEC) is important. This condition causes symptoms ranging from mild diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis and, in almost 10% of patients (especially risk groups such as children and the elderly), this infection may become a high-risk disease known as Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). This syndrome is often associated with the expression of cytotoxins known as verotoxins (VT) or shigatoxins (Stx). For example, one of the most common serotypes that generates the greatest concern to public health belongs to this group and is none other than Escherichia coli O157:H7. This serotype is closely related to food-borne illnesses, resulting in a high incidence of EHEC infections and deaths each year.

Virulence mechanism in enterohemorrhagic strains. Shiga toxin and others

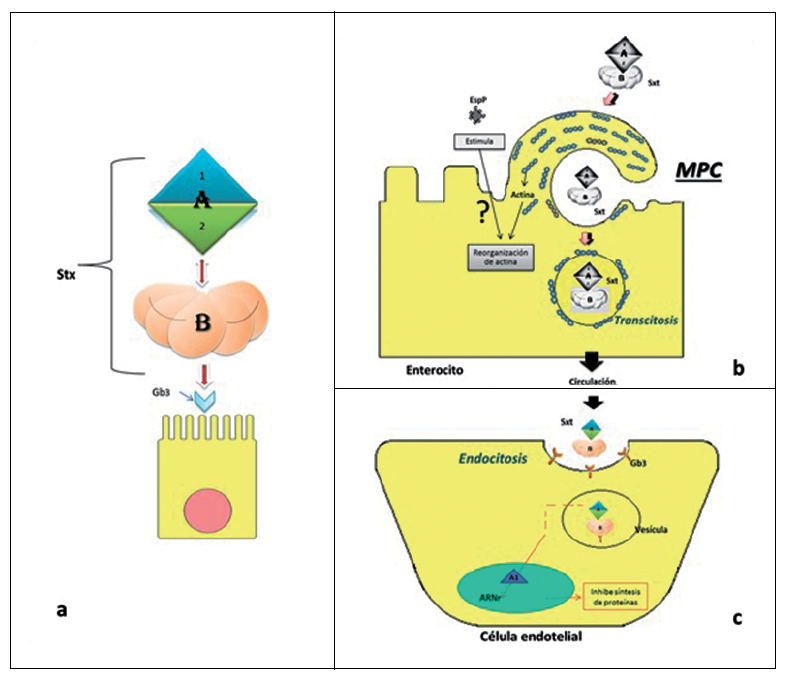

At a structural level, the Shiga toxin is composed of a subunit A and a subunit B. At the same time, subunit A is divided into two distinct parts, A1 (cytotoxic) and A2 (structural).

As the diagram shows, the Shiga toxin enters in the intestinal endothelium, at a cellular level, due to the affinity of its subunit B with membrane receptors, thus activating the toxin's macropinocytosis. Once inside the cell, it is transported through vesicles by cytoplasm. Subunit A1's toxic activity is performed at a ribosomal RNA level, blocking protein synthesis and resulting in cellular death.

PO157 plasmid is also a virulence factor, among others. This plasmid is present in O157:H7 strains and integrates genetic material for the production of other factors related to cell adhesion, degradation of mucins and glycoproteins or regulation of inflammatory and cytotoxic processes.

In relation to the presence of this PO157 plasmid in some strains, the capacity of Escherichia coli to exchange genetic material through mobile genetic elements has been observed, providing a very high environmental adaptability to the bacterium. These factors are believed to contribute to the emergence of intestinal pathogens, with improved survival and persistence in food systems. It also demonstrated the relative ease with which these bacteria exchange genetic material. In the case of O104:H4 strains, they are responsible for the breakout in Germany, in May and June 2011. This strain was found to contain genetic material from human cell enteroaggregative strains, genes from animal pathogenic enterohemorrhagic strains, as well as resistance to many antimicrobial substances.

Contamination origins in humans

Escherichia coli's origin is almost exclusively fecal and is therefore transmitted through contamination of food and water with material of that origin. Other pathways, such as cross-contamination or direct human contact during food processing, again show that the focus of infection of this bacterium is the consumption of contaminated food and water.

But, then, how is food contaminated with Escherichia coli?

A wide range of foods can be vehicles for the pathogenic strains of this ubiquitous bacterium. Food can be contaminated either directly or by cross-contamination, as discussed in the previous point. Contamination may occur during the growth and cultivation of vegetables where manure is used, or even during milk collection or meat processing. Additional sources of contamination may also occur during post-harvest handling, transport, processing and unhygienic handling during food preparation.

One of the factors contributing to the persistence of E. coli at different levels of the food chain is inadequate control of the processing parameters of different foods, which may include pH, water activity (aw), and storage at temperatures that allow these bacteria to grow.

And what foods are the main sources of transmission? These range from raw and poorly processed meat (such as fermented meat or undercooked minced meat) to dairy products and unpasteurized fruit juices such as raw vegetables. In fact, it is more and more frequent to find sources of contamination in this last type of food, such as the one that occurred during 2011 in Germany due to the appearance of STEC O104:H4 strains in the aforementioned breakout.

Animal products

1.jpg)

Although prevalences have been described in some wild and game animals, the main reservoir belongs to ruminant animals. Specifically, bovine origin is considered as the main source of contamination of STEC and EHEC strains (O157:H7). Although these microorganisms can produce diarrhea in younger specimens, they behave as harmless commensals of the intestine in adult individuals, without causing medical conditions.

Meat contamination generally occurs during the slaughtering of livestock, due to bad practices, as well as slaughterhouse hygiene and handling. The activities that most frequently contaminate meat during processing are skin removal, intestinal spillage and general site sanitation.

Fresh products and sprouted seeds

_1.jpg)

E. coli may enter agro-systems through manure, irrigation water, contaminated seeds, insect pests, domestic animals or nematodes. In addition, it has been established that these bacteria can survive in soils for up to 20 months, and thus remain as an environmental contaminant for an extended period of time. Microorganism survival is even greater in leaves and roots.

In recent years, the popularity among consumers of sprouted seeds has increased significantly due to their high nutritional value. However, reports of diseases caused by these foods have raised concerns among public health agencies and consumers, which will lead to increased control measures on raw vegetables and sprouted seeds.

Actions taken by regulatory bodies with regard to the incidence of Escherichia coli

Although in 1998 the European Union created the network for Epidemiological Surveillance and Control of Communicable Diseases, it was not until 2009 that enterohemorrhagic E. coli infections were recognized as a food-borne disease under Directive 2009/312/EC. As a result of this provision, STEC infection case data should be reported quarterly to the European Surveillance System.

Although most countries focus on notification and surveillance of serotype O157, according to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), such actions should be extended to other more frequently identified serogroups as well, mainly O26, O103, O104 and O145.

On the other hand, Regulation (EC) No. 2073/2005 and its amendment No. 1441/2007, concerning microbiological criteria applicable to food products, has established a safety criterion for E. coli in different food categories, being used as a food safety criterion, hygiene criterion and fecal contamination indicator. To do this, a plate count is performed using a validated microbiological method. This regulation also establishes reference methods based on ISO such as 16649-1, 16649-2 and 16649-3.

Despite all these regulations, it is necessary to establish microbiological guidelines and control plans with the objective of reducing fecal contamination along the food chain, thus reducing risks to public health.

Not only should these plans reach producers and marketers, but the World Health Organization (WHO) has established a guide entitled "Five Keys to Safer Food Manual" for good practices at home. It sets out good hygiene practices that will help prevent the transmission of diseases.

It is clear that Food Safety is a global issue that concerns us all.

CONDALAB to Exhibit at WHX Labs Dubai 2026

CONDALAB to Exhibit at WHX Labs Dubai 2026

Food fraud: How do we detect it?

Food fraud: How do we detect it?

Visit Us at MEDICA 2025 – Discover Our Precise Detection Solutions

Visit Us at MEDICA 2025 – Discover Our Precise Detection Solutions

PCR: The Technique Revolutionizing Rapid Detection in the Food Industry

PCR: The Technique Revolutionizing Rapid Detection in the Food Industry

How Culture Media Ensure the Safety, Efficacy, and Quality of Medicines

How Culture Media Ensure the Safety, Efficacy, and Quality of Medicines