Published: 23/08/22 12:56 Categories: Microbiology

Last June in Spain, an investigation was made into a possible case of cholera, the first in the country for more than 40 years, after an underage girl tested positive for cholera after drinking tap water on a farm.

Is there a risk of a new cholera outbreak in Europe?

Vibrio cholerae is one of the major water- and food-borne pathogens of major global health concern as it is historically responsible for a large number of pandemics.

And despite the fact that most developed countries have virtually eradicated cholera successfully, thanks to monitoring and hygiene programs implemented by health systems and vaccination, recent years have seen a trend of increasing cases in parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America, as a result of insufficient or lack of access to safe water, with cholera being used as an indicator of social inequity.

In this specific case, samples were taken from the suspected contaminated source to identify the contaminating agent, and after analysis, it was determined that the presence of Vibrio cholerae non-toxigenic O1 in the water was a case of gastroenteritis, and not cholera, as initially speculated.

Are gastroenteritis and cholera the same thing?

This has led to confusion, since, although cholera is a disease caused by the bacillus Vibrio cholerae, there are pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains, the latter being the cause of cholera.

The most common pathogenic serotypes to have been identified are O1 and O139. Both hace the ability to secrete cholera toxin (CT), a protein that causes the main symptoms of this disease, such as loss of electrolytes and water. However, it is not the only protein, as there are other toxins that also contribute to the pathogenesis of cholera.

The most frequent vehicle for the transmission of this disease is contaminated water, not just its consumption but also its use in the watering of fruits and vegetables. However, this is not the only source, since other seafood products such as fish, shellfish, crustaceans and mollusks have been identified as the cause of outbreaks in Japan, the USA and the Philippines.

Detection of V. cholerae and V. parahemolyticus according to ISO 21872

Studies have been made of the survival of Vibrio cholerae O1 and non-O1 in multiple foods such as dairy products, meats and poultry, grains, spices and eggs, and it has been found that these gram-negative bacteria could survive for days and even weeks under extreme conditions such as refrigeration or after products have been subjected to cooking processes.

Another highly important aspect at present is the role of the climate crisis, as an increased prevalence of outbreaks associated with Vibrio spp. has been observed in Europe during unusually warm periods or in times of higher than usual temperatures.

So it should come as no surprise if Vibrio cholerae is included as one of the pathogens of mandatory analysis in the food industry in the not-too-distant future.

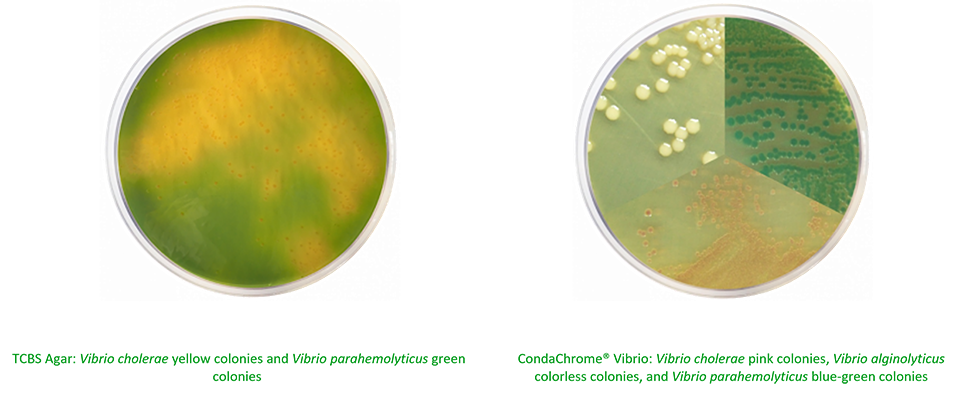

For this purpose, culture media such as ISO Alkaline Peptone Water for the enrichment and TCBS Agar to isolate colonies present in the sample, and even alternative media, such as our own CondaChrome® Vibrio for a quick and easy identification of various strains of Vibrio spp. as V. alginolyticus, V. parahemolyticus, V. vulnificus and of course V. cholerae.

What do you think about the monitoring of Vibrio cholerae in food? If you need any information, please do not hesitate to contact us, and we will be pleased to help you.

Probiotics: Which ones are good?

Probiotics: Which ones are good?

Condalab Says YES to the World’s Leading Lab Trade Fair: Analytica 2026

Condalab Says YES to the World’s Leading Lab Trade Fair: Analytica 2026

CONDALAB to Exhibit at WHX Labs Dubai 2026

CONDALAB to Exhibit at WHX Labs Dubai 2026

Food fraud: How do we detect it?

Food fraud: How do we detect it?

Visit Us at MEDICA 2025 – Discover Our Precise Detection Solutions

Visit Us at MEDICA 2025 – Discover Our Precise Detection Solutions